Introduction

If we liken Chinese calligraphy and paintings to a surging river originating from immemorial time, the calligraphy and paintings in Ming and Qing dynasties would be a stream with energetic rhythms. Although having no mysteries like in Shang and Zhou dynasties, or grandiosities in Han and Tang dynasties or elegance in Song and Yuan dynasties, these calligraphic works and paintings in the Ming and Qing dynasties with different styles are flowing like limpid brooks, inspiring lofty sentiments.

The exhibited calligraphic works and paintings in the Ming and Qing dynasties represent a variety of schools in landscape paintings, flower-and-bird paintings and figure paintings. In the Ming Dynasty, Zhe School created by Dai Jin emphasized shapes and expressions of deep meanings with simple techniques, having boldness and originality behind seriousness and precision. The “Four Masters of Wumen School”- Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, Tang Yin and Qiu Ying- reinvigorated literati painting. They created a style that stressed poetic charm, serene elegance, and calm grace. Songjiang School initiated by Dong Qichang stressed elegant and mellow techniques, simple atmosphere and uninhibited conception. Yunjian School created by Shen Shichong advocated imitation of ancient masters and elegant brushwork. Wulin School led by Lan Ying was vigorous and sedate, while Jiaxing School headed by Xiang Shengmo was elegant and graceful. Each of these schools was fascinating in its own way.

In the Qing Dynasty, under the influence of literati painting, painters advocated ‘literati taste’, learning from nature and expressing personalities. The Orthodox School, represented by Four Wangs—Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui and Wang Yuanqi, focused on the imitation of ancient masters, venerating Dong Qichang and stressing brush-stroke techniques. In contrast, the Reformist School, headed by ‘Four Monks’, one of whom was Zhu Da (Bada Shanren), was opposed to the conventional way and the imitation of ancient styles. In the mid Qing Dynasty, Yangzhou School, led by Eight Eccentrics, used painting to give vent to their pent-up emotions and embody noble characters, expressing profound ideas with flexible techniques. In the late Qing Dynasty, Shanghai School carried on the freehand-flower tradition initiated by Chen Chun and Xu Wei and incorporated techniques of calligraphy and seal cutting to break a new ground for literati painting.

Schools like these are like several streams flowing among lofty mountains and wide plains and finally converged into the mainstream of the literati painting with successive waves.

Taige Script was widely practiced in the early Ming Dynasty. In the mid Ming Dynasty, Wumen Calligraphic School, led by Zhu Yunming and Wen Zhengming, advocated literati calligraphy and prevailed for a time. The most famous calligraphic school in the Ming Dynasty was the one composed of four masters - Dong Qichang, Xing Dong, Zhang Ruitu and Mi Wanzhong. Of them, Dong made the greatest influence with his graceful style.

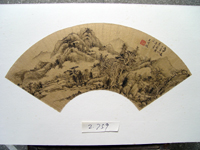

In early Qing Dynasty, tieshu and cursive-running script prevailed in calligraphy and formed the “Gaunge Script”. In the mid and late Qing Dynasty, the unearthing of a large number of metal and stone steles, Han bamboo slips, and oracle bones gave rise to Stele Studies. Bronze inscription script, seal character and official script were all taken to unprecedented heights, which resulted in new compositional and brush-stroke techniques, contributing to the development of cursive-running script. Wang Duo's cursive-running script was creditably the representative of calligraphy in the early Qing Dynasty with bold and generous charms. Even Zhao Mengfu and Dong Qichang could not compete with him. In the late Qing Dynasty, Stele Studies had become the dominant approach to calligraphy. Its influence continues to be felt today.

These exhibited calligraphic works and paintings in the Ming and Qing dynasties have gathered traditional elements and contained literati flavors. Careful savoring is needed to appreciate their charms and conceptions expressed by each and every stroke.

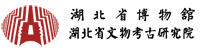

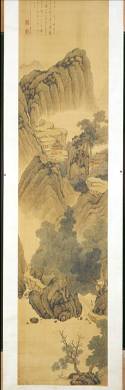

Landscape Scroll, created by Dong Qichang (1555-1637), has a simple composition, vigorous strokes and light, elegant ink color, with graceful mellowness behind simplicity. It exudes a serene and leisurely ambience.

In Enjoying the Cool Shade under a Pine by Ding Yunpeng (1547~1628), the blue pine branches inspire a feeling of serenity and coolness; the elderly man reclining on the rock and three children, two playing with water and the other one looking back at him, form an interesting contrast between stillness and movement. The composition is spacious, highlighting the theme; the figures, trees and rocks are elaborate and lifelike.

In Landscape Fan Covering in Ink by Wang Shimin (1547~1628), the mountains and groves are depicted with light lines, fine and dense dots, alternate types of light-ink strokes and a variety of brushstrokes, which convey a classical simplicity.

Wang’s best calligraphic works are those in running cursive script. His cursive script, in the style of great xieyi, is overwhelmingly majestic, for which he was regarded by Lin Sanzhi as ‘the greatest master of cursive script after Huai Su in the Tang Dynasty’. His running script, which is reserved and full of variations, expresses his personality with flowing lines and boldly produces a clear-cut visual effect with contracts between lines and black patches, creating a throbbing rhythm. Despite its rustic appearance, Wang Duo’s calligraphy is full of vitality.

Two Poems on a Thin Horse, created by Zhang Ruitu (1570—1644) who held the position of the first-rank official, emphasized horizontal brushwork and compositions of characters despite their vertical arrangement; the oblique strokes and sharply bent strokes are highlighted to convey the artist’s emotional variations, producing a general effect of natural smoothness.

Zhang Yin (1761—1829) was particularly skilled at painting pines, which were known as Zhang Pines. This Landscape Scroll is a bird’s eye view, featuring distant mountains shrouded in thick fog and a river meandering between rolling mountains overgrown with verdant trees. There are prosperous pines and trees in varied postures along both sides of the river, which make the whole picture appear romantic, serene and lively. The painting, simple and elegant, is typical of “Jingjiang School”.

Overview

Enjoy Ming and Qing Works Taste Rich Literati Flavor

Zhang Xiu, Hubei Provincial Museum

The Exhibition of Ming and Qing Paintings and Calligraphic Works presents different schools of calligraphy and paintings, such as the Zhe School in the Ming Dynasty and Wulin School in the Qing Dynasty. We will display in the Calligraphy and Painting Hall the best works of different periods and schools. Welcome to the journey of Chinese calligraphy and paintings.

First let us take a look at landscapes by Dai Jin (1388~1462), the founder of Zhe School. He carried on the majestic style of Southern-Song ink-and-wash painting; he was greatly influenced by Li Tang, and also learned from Dong Yuan. In addition, he was good at integrating and innovating. In composition he stressed the whole picture, dividing scenes diagonally. His brushstrokes fall into two broad categories—running ink and axe-cut strokes. Though he was an accomplished painter, he was not so well trained in writing as to be able to grace his masterworks with poems or essays.

L• Ji (about 1439 -1505) was an imperial-court painter in the Ming Dynasty. His flower-and-bird paintings display not only a painter's skills and styles but also literati tastes. L• and Lin Liang (circa 1426~after 1493), jointly known as Southern Lin and Northern L•, were regarded as peerless masters. L• favored meticulous-style paintings in deep colors. He was also skilled at ink-and-water freehand flowers and birds. His style is marked by bright colors and vivacious shapes. In his central scroll Green Bamboos and White Crane, the crane, spreading its wings, is graceful and lifelike; the bamboos and feathers are elaborate and lively. The colors are bright; the green bamboo leaves and black rocks set off the whiteness and gentleness of the crane, and highlight the harmony between movement and stillness.

In the mid Ming Dynasty, Wen Zhengming from Wumen School, often painted landscapes with fine brushstrokes in an elegant style; sometimes he also used heavy strokes for candid expression of simple yet majestic conceptions. As one of the four master of Wumen School, Qiu Ying stressed on conceptions, mellow brushwork, elaborate and accurate depiction of objects, and his works suit both refined and popular tastes. In his horizontal scroll Becoming an Immortal, which is shown at this exhibition, the ladies are beautiful and graceful, with natural expressions and in a variety of postures; the use of meticulous-style paintings in deep colors is reminiscent of Tang and Song illustrations of stories.

In the late Ming Dynasty, Wumen School gave way to Dong Qichang. His prestige as Minister of Rites and a celebrated artist, plus his being favored by emperors Kangxi and Qianlong, made him the leading painter among his contemporaries. He said that a painter should ‘read a thousand books and travel ten thousand li’. His created Songjiang School, which took over the prevalence of Wumen School. His album Landscape Album in Ink, painted on gilded paper, expresses ancient aesthetic values with a Zen-like stress on detachment.

Known as the ‘Rearguard of Zhe School’, Lan Ying (1586~circa 1666) established the “Wulin School”. He exhibited a strong literati inclination, jotting down his ideas about painting and impromptu poems, which blend naturally with his paintings. In the inscriptions on some paintings, Lan Ying would specify that he was imitating the styles of some other masters. Actually, these works are in his own style.

Lan Shen learned painting from Lan Ying, his grandfather. His Landscape Scroll reflects that he imitated the fine-stroke landscape as practiced by Lan Ying in his middle age, with more elegant brushwork.

Xiang Shengmo (1597 - 1658) integrated the precise brushwork of Song painters and the charming style of Yuan artists in his landscapes. He was especially fond of painting pines, for which he was said to be well-known across southeast China.

Ding Yunpeng (1547~1628) was the greatest Ming painter of Buddhist and Taoist figures. His plain-line arhats is vivid and lifelike. Dong Qichang, who admired them for their elaborateness, presented Ding with a seal with the characters hao sheng guan, meaning ‘extremely accurate’. In Enjoying the Cool Shade under a Pine, the blue pine branches inspire a feeling of serenity and coolness; the elderly man reclining on the rock and children with different expressions form an interesting contrast between stillness and movement and highlight the theme.

Wang Shimin (1592~ 1680) was the founder of Wulin School. His paintings are characterized by a fresh, graceful style and fine, mellow brushstrokes. In his Landscape Fan Covering in Ink, the mountains and groves are depicted with light lines, fine and dense dots, alternate types of light-ink strokes and a variety of brushstrokes, which convey a classical simplicity.

Wang Hui (1632~1720) was instructed in painting by Wang Jian and Wang Shimin. In his forties his painting techniques got mature as a master of painting, and he was more successful among the Four Wangs. His Landscape Scroll, which is shown at the exhibition, is marked by his characteristic fine, elegant brushwork and heavy, mellow ink. His styles were followed by a number of artists, who formed Yushan School.

Though ‘finger painting’ was said to have originated in the Tang Dynasty, it had never been well developed until the reign of Kangxi, when Gao Qipei (1660~1734), assistant minister of punishment, perfected it so that it could be applied to figures, landscapes, flowers, birds and animals. His Landscape Scroll is marked by the skillful control of ink colors and the use of thick and thin lines to represent the fluffy features of birds and the vigor of trees.

Bian Shoumin (1684~1752) was good at capturing the charms of wild geese with simple strokes.

The cursive-script calligraphy by Wang Duo (1592~1652) is overwhelmingly majestic. His cursive script was full of varieties. His running script, which is reserved and full of variations, expresses his personality with flowing lines and boldly produces a clear-cut visual effect with contracts between lines and black patches, creating a throbbing rhythm. Despite its rustic appearance, Wang Duo’s calligraphy is full of vitality.

Two Poems on a Thin Horse, created by Zhang Ruitu (1570—1644) who held the position of the first-rank official, emphasized horizontal brushwork and compositions of characters despite their vertical arrangement; the oblique strokes and sharply bent strokes are highlighted to convey the artist’s emotional variations, producing a general effect of natural smoothness.

This exhibition also presents the Landscape in Light Red by Wang Jian, Yuefu Poems in Cursive-running Script by Wang Shizhen and other masterpieces. If you are interested, you may appreciate them once more. If you could identify yourself with them, you may grasp the essence of Ming and Qing calligraphic works and paintings.